Biography

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald 1900-1948

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald (1900-1948) was an artist, writer, and personality who helped to establish the Roaring Twenties image of liberated womanhood embodied by the “flapper.” She and her husband, novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940), became icons of the freedoms and excesses of the 1920s Jazz Age and symbols of the emerging cultural fascination with youth, conspicuous consumption, and leisure. Best known for her extravagant public persona and descent into mental illness, she is also remembered as an artist and author in her own right, and both her vivacity and tragedy live on in the many characters she inspired in her husband’s novels and short stories.

Born on July 24, 1900, in Montgomery, Zelda Sayre was the youngest child of Alabama Supreme Court Justice Anthony Dickson Sayre and Minnie Buckner Machen Sayre, a prominent middle-class couple with roots in both Montgomery and Confederate history. (Judge Sayre’s uncle William was a prominent Montgomery merchant whose home eventually became Jefferson Davis’s first White House; Minnie Sayre’s father was a Kentucky senator in the Confederate Congress). By her early adolescence, Zelda—named after the gypsy heroine of an obscure 1874 novel—was already a formidable presence in Montgomery social circles, starring in ballet recitals and basking in the glow of elite country club dances.

At such a dance in July 1918, barely a month after graduating from Sidney Lanier High School, Zelda met F. Scott Fitzgerald, a 21-year-old army second lieutenant stationed at nearby Camp Sheridan. Despite Scott’s claim that he was on the verge of literary fame, Zelda doubted his financial prospects and entertained several other suitors, much to the chagrin of the aspiring author, who continued to press for an engagement. Zelda’s tactics fueled Scott’s insecurities, and the motif of a young man pursuing an elusive and conniving woman would later come to define his fiction.

In early 1920 prominent New York publisher Charles Scribner’s Sons accepted Scott’s first novel, This Side of Paradise, and Zelda finally accepted his proposal of marriage. The couple wed in New York on April 3, 1920, just as the book began to ignite a scandal for its portrayal of the free-wheeling lifestyle and relaxed morals of what became known as the “Lost Generation.” As the presumed inspiration for character Rosalind Connage, Zelda became an instant celebrity; and for the first half of the 1920s, she frequently contributed her opinions on modern love, marriage, and childrearing to an eager media. In 1921, Zelda gave birth to the couple’s only child, Frances “Scottie” Fitzgerald. Scott used her reaction to the birth in The Great Gatsby when Daisy Buchanan states in response to the birth of her daughter: “I’m glad it’s a girl. And I hope she’ll be a fool—that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool.”

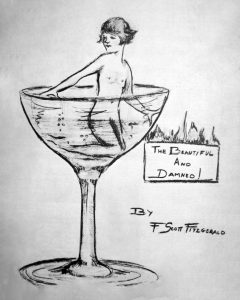

Zelda’s influence on Scott’s fiction in this period is inestimable. In addition to inspiring his major heroines, she supplied him with many other memorable lines, including an evocative description of Montgomery’s Oakwood Cemetery that appears in his short story “The Ice Palace.” When Scott’s novel The Beautiful and Damned was published, the New York Tribune hired Zelda to review it, she hinted that a passage in the book was lifted straight from her missing diary.

Such statements have fueled scholarly debate that Zelda was Scott’s de facto collaborator and that he appropriated her personal experiences in his work. Such charges were given additional weight by the frequent addition of his name to her bylines on nearly two dozen stories and articles she produced between 1922 and 1934. In fact, Scott’s agent or editors added his name in several instances without his knowledge because the joint byline increased the price that these works received from leading magazines. Claims that Zelda “co-authored” her husband’s writing certainly are exaggerated, but few would deny that her personality was (and remains) key to its appeal.

By the late 1920s, the Fitzgeralds’s highly publicized and often stormy relationship began to break down as Zelda sought outlets for her own creativity. In addition to writing, she returned to two childhood passions—art and dance. In 1930, stress resulting from her frustrated attempts to become a professional ballerina led to the first of what would be many psychological breakdowns. (Although Zelda was treated for schizophrenia, mental-health experts later would contest both the diagnosis and recovery regimen prescribed by her main physician, Dr. Oscar Forel). From June 1930 to September 1931, Zelda lived at Les Rives de Prangins Clinic in Nyon, Switzerland. After her release, the couple returned to Montgomery and rented a home in the city’s Old Cloverdale neighborhood (the home is now the Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum).

Scott soon left for Hollywood, and in February 1932 Zelda entered Johns Hopkins University’s Phipps Clinic, where she completed her only novel, Save Me the Waltz, an autobiographical recounting of her unstable marriage. Scott deeply resented the book, blaming the financial burden of her hospitalization for his inability to complete Tender Is the Night, and he also accused Zelda of poaching its plot for her novel. When her novel failed to garner critical or commercial interest (royalties amounted to a paltry $120), Zelda abandoned her literary aspirations. She then tried writing for the stage and produced the unsuccessful comedy Scandalabra, mounted by an amateur drama troupe in Baltimore in 1933. It was her last public writing effort. Zelda next turned to painting, but she fared no better. A 1934 show of her work in New York inspired a condescending notice in Time magazine that described the event as her “latest bid for fame” and her canvases as “the work of a brilliant introvert.”

Morgan Le FayThe Fitzgeralds parted ways in 1934, although they never divorced. (Their daughter was largely raised by nannies before entering boarding school). From 1936 to 1940, Zelda resided at Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, and Scott descended into alcoholism and literary obscurity, eventually relocating to Hollywood in the hope of establishing himself as a screenwriter. He died of a heart attack there on December 21, 1940.

That year, Zelda returned to Montgomery, where she lived under the care of her mother. In addition to painting, she took occasional dance lessons and began a second novel entitled Caesar’s Things, which remains unpublished. She returned occasionally to Highland Hospital when her depression became debilitating and was one of nine women killed on the night of March 10–11, 1948, when a fire swept through the hospital’s main wing.

Zelda’s final years coincided with her husband’s posthumous rediscovery as a significant American writer. Early F. Scott Fitzgerald biographers and critics tended to depict Zelda as equal parts liability and inspiration. Negative opinion culminated with the 1964 publication of Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, in which he portrays a fictionalized Zelda as a harridan who derailed her husband’s career.

In Nancy Milford’s 1970 bestselling biography Zelda, she is a symbol of thwarted artistry, however—a theme echoed by many feminists, who see her frustrated attempts to establish herself as an artist as exemplifying the struggle women face in finding outlets and acceptance for their creativity. In recent years, scholars have both taught and written about Save Me the Waltz with increasing frequency, and exhibitions of Zelda’s surviving artwork regularly travel the United States. The Fitzgeralds’ story—of which Alabama is an indelible part—continues to fascinate scholars and the general public and has inspired an array of academic studies, movies, documentaries, and even musicals.

Additional Resources

Bruccoli, Matthew J., ed. The Collected Writings of Zelda Fitzgerald. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1991.

Cline, Sally. Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise. New York: Arcade Publishing, 2003.

Kurth, Peter, Jane S. Livingston, and Eleanor Lanahan, eds. Zelda: An Illustrated Life: The Private World of Zelda Fitzgerald. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

Milford, Nancy. Zelda: A Biography. New York: Harper & Row, 1970.

Wagner-Martin, Linda. Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald: An American Woman’s Life. London: Palgrave, 2004.