ENJOY OUR SOCIETY PODCAST:

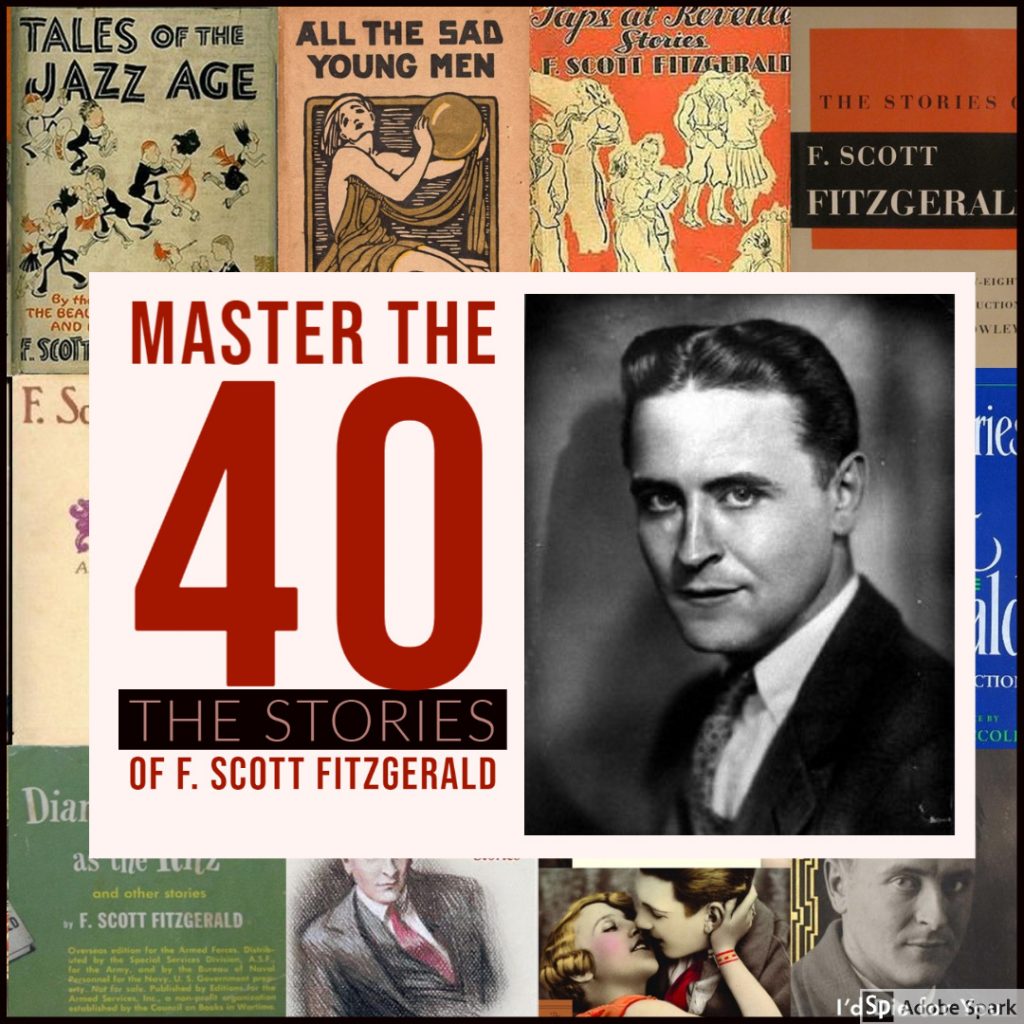

In 1929 F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote Ernest Hemingway that because his short stories now earned $4000 a pop he was “an old whore” who had “mastered the 40 positions” when “in her youth one was enough.” But were the upwards of 180 stories he cranked out when not writing The Great Gatsby really the work of a literary prostitute selling out his talent for a fast buck? Kirk Curnutt and Robert Trogdon don’t think so. Each episode they draw a random title from a hat and explore its place in Fitzgerald’s career, in the magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post or Esquire where it may have appeared, and in the overall development of the American short story. Along the way, they talk literary politics, history, and gossip from the 1920s and 1930s, rediscovering the lively personalities and rivalries that tried to define the porous boundaries between commercial and artistic fiction, between the popular and the avant-garde, between the forgotten and the canonized.

Our Most Recent Episodes:

“John Jackson’s Arcady” (Saturday Evening Post, July 26, 1924)

Some critics have dismissed this story of a man who escapes his worldly woes by fleeing his office to return to his small-town, rundown origins as “pure trash,” but we uncover some historical reasons it should be of interest. First, “John Jackson’s Arcady” was the last short story Fitzgerald wrote in April 1924 before departing for the Riviera to write The Great Gatsby. As such, it has some intriguing overlap with the novel. Second, although not republished in a collection until 1979, the story enjoyed a curious afterlife as an elocution text for aspiring high-school orators (and Rotarians). But third and most importantly, the story’s closing scene in which John Jackson discovers just how much the world appreciates the good deeds he’s done may just be—oh heck, we’ll go on a limb and say we’re ninety percent certain it is—the inspiration for Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, starring (of course!) Jimmy Stewart. We explore that tantalizing connection, as well situate the story in the very popular 1920s’ genre of the “revolt from the village.” We also ask why “Arcady” is the rare sympathetic portrait of an American businessman at a time when nonfiction bestsellers such as Bruce Barton’s The Man Nobody Knows (1925) proclaimed Jesus the quintessential entrepreneur. Along the way, after figuring out how to pronounce “Arcady,” we quiz each other on famous Jacksons, from Stonewall to Tito to Luscious.

“The Lost Decade” (Esquire, December 1939)

Our eighth episode focuses on the shortest short story Fitzgerald ever published, “The Lost Decade,” which clocks in at only 1,100 words, making it Depression-era kin to today’s flash fiction. Appearing in Esquire in December 1939 (exactly one year before the author’s death), “Decade” is a haunting masterpiece of intimation and mood: eminence grise Matthew J. Bruccoli summed it up perfectly when he called it “elliptical.” Told from the perspective of a New York City newspaper “call boy,” Orrison Brown, the story focuses on an architect, Louis Trimble, who wanders the metropolis seeking to reestablish contact with the fleeting sights and sounds of real life. Not until the end of the piece do we learn Trimble is newly sober after an entire decade in an alcoholic stupor. The story’s stoic tone is a perfect metaphor for both Fitzgerald’s and America’s struggle to survive the psychic shocks of the 1930s. We compare “The Lost Decade” to other representations of alcoholism in Fitzgerald’s fiction, exploring what in the story is new, and we connect its New York setting to a stirring nonfiction ode to Gotham Fitzgerald penned only a few years earlier, “My Lost City.”

“At Your Age” (Saturday Evening Post, August 17, 1929)

Our first episode of 2021 examines a story that has been completely ignored both by fans and scholars: August 17, 1929’s “At Your Age.” The lack of interest is curious for a couple of reasons. For starters, this tale of a fifty-year-old bachelor, Tom Squires, confronting age-inappropriate behavior as he chases after a debutante thirty years his junior was the submission that earned Fitzgerald his peak price of $4,000 per story from The Saturday Evening Post. His agent, Harold Ober, even called it the best story FSF had ever written. That’s not true, of course, but we owe “At Your Age” a debt of gratitude given that the hefty raise it occasioned inadvertently inspired the title of this podcast: it was after that $4,000 milestone that Fitzgerald wrote the famous letter to Hemingway calling himself an “old whore” who had mastered the forty positions popular fiction demanded of authors. But “At Your Age” is also important because it explores from a mature perspective the albatross that clung to a writer who made teenage petting parties famous: the idea that he was so obsessed with remaining young that he never grew up. We put both Tom Squires’s obsession with Annie Lorry and Fitzgerald’s own age consciousness in a cultural context, exploring many of the crazy, often fraudulent remedies designed to stave off the waning vigor and potency that supposedly mark the midlife. From facelifts to monkey gland injections, the Jazz Age was obsessed with staying forever young; while “At Your Age” may lament the aging process, it critiques the undignified, foolish ways men in particular have pursued what William Butler Yeats called the “second puberty”—including what from a post-Philip Roth perspective we would consider the rather icky attraction to younger women.

“Pat Hobby and Orson Welles” (Esquire, May 1940)

Hot on the heels of David Fincher’s Mank, a hotly disputed retelling of the origins of Citizen Kane, we explore F. Scott Fitzgerald’s own take on the rise of Orson Welles. In the final year of his life, without income from Hollywood studios or loans from his longtime agent, Harold Ober, Fitzgerald supported himself by cranking out seventeen short stories about the Hollywood hack Pat Hobby, which he sold to Arnold Gingrich’s Esquire for $250 each. (Five of the stories appeared posthumously). The most historically interesting of the series is May 1940’s “Pat Hobby and Orson Welles,” which pokes fun at Old Hollywood’s fear and trepidation at the arrival in Tinseltown of the wunderkind notorious for his 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast. Fitzgerald’s story appeared in print just as Herman Mankiewicz completed a 267-page doorstop draft called American, which Welles shortly shaped into a withering assault on William Randolph Hearst that ensured we would never hear the name “Rosebud” the same way again. The filmmaker that the hapless scrapper Pat Hobby must contend with has thus not yet made the most celebrated movie in American cinema. Rather, Welles is known for the extravagant contract RKO offered him in 1939, including a $150,000 salary and authority over the final cut. Strangely enough, what gossip columnists are most curious about is the boy wonder’s newly grown beard, which threatens old-timers like Pat as much as the changes to the studio system his arrival augurs. As we discuss the legacy of the Pat Hobby stories and their relationship to The Love of the Last Tycoon, the Hollywood novel left incomplete by Fitzgerald’s premature death in December 1940, we debate auteur theory, the Hollywood production process that Fitzgerald at once loathed and idealized through his adoration of Irving Thalberg, and the creative parallels that have saddled Fitzgerald, Welles, and Mankiewicz with the troublesome label “genius.”